An invitation to be fascinated with what builds enough courage to engage with our world.

Interested in our initiative? Submit your email to receive an invite to the alive collective.

Menu

Interested in our initiative? Submit your email to receive an invite to the alive collective.

An invitation to be fascinated with what builds enough courage to engage with our world.

Written by Johanna Lynch – University of Queensland

I have an issue with the term ‘resilient’. It seems like just another way to objectify a person. In some ways it is similar to the word ‘vulnerable’ when used to describe someone else from the outside– rather than the whole human condition. These describing words seem judgemental to me: one praising a version of ‘normal’, one a polite putdown when used in particular ways. Both are very thin descriptions of complex people from the point of view of other people. Both lay responsibility on the individual for very complex communal processes. Both imply something about weakness, effort, and moral fortitude. Both miss the whole picture.

The word resilience has snuck into healthcare in a similar way to depression. They describe abstract processes and complex social phenomena as nouns that supposedly reside inside people.1 They individualise and simplify in a way that is irresponsible and not evidence based. 2,3. According to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, resilience now means: “the capability of a strained body to recover its size and shape after deformation caused especially by compressive stress” and “an ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change”. Wright et al describe it as “positive adaptation in the face of risk or adversity”. They also describe it in a less individualised and more systemic way as a “capacity of a dynamic system to withstand or recover from disturbance”.4

I can see a positive intention in using the word ‘resilient’ to notice the strengths of a person and their innate capacity to heal or recover despite hardships. So, it seems counter-intuitive to not support the move towards ‘resilience-training’ and ‘developing a resilience mindset’ that are now part of many mental health settings. It seems a strong and worthy goal of care. Doesn’t it?

Except it leaves out so many parts of the whole person. It leaves out their context and history; their relationships and culture; what suffering and injustice they and their community have endured; what gives them meaning; and it can mask the potential paradox of inner distress coexisting with the outer appearance of function. While championing growth, it leaves out community and it continues the isolationary individualising of care that is part of the legacy of psychiatry and cultures that overvalue individuality and personal agency. 3

This focus on the individual and their capacity to ‘bounce back’ seems especially harmful in the context of communities who have experienced generations of ‘compounded trauma’ after colonisation or other forms of injustice (thank you to Uncle Richard Fejo from Larrakia Country for this wording, communicated by Phillip Orcher). It seems a callous cruelty for a privileged observer to dare to assess an individual’s ‘resilience’ in those settings. I would say that some of my most distressed patients never get called ‘resilient’ and yet they have overcome so much – more than I think I could face and still be standing. This group of patients also sometimes have their personality and families over generations critiqued from outside, completely ignoring that impact of what they have had to endure. As trauma therapist and author of My Grandmother’s Hands, Resmaa Menaken says:

“Trauma in a person, decontextualised over time, looks like personality. Trauma in a family, decontextualised over time looks like family traits. Trauma in a people decontextualised over time, looks like culture.”

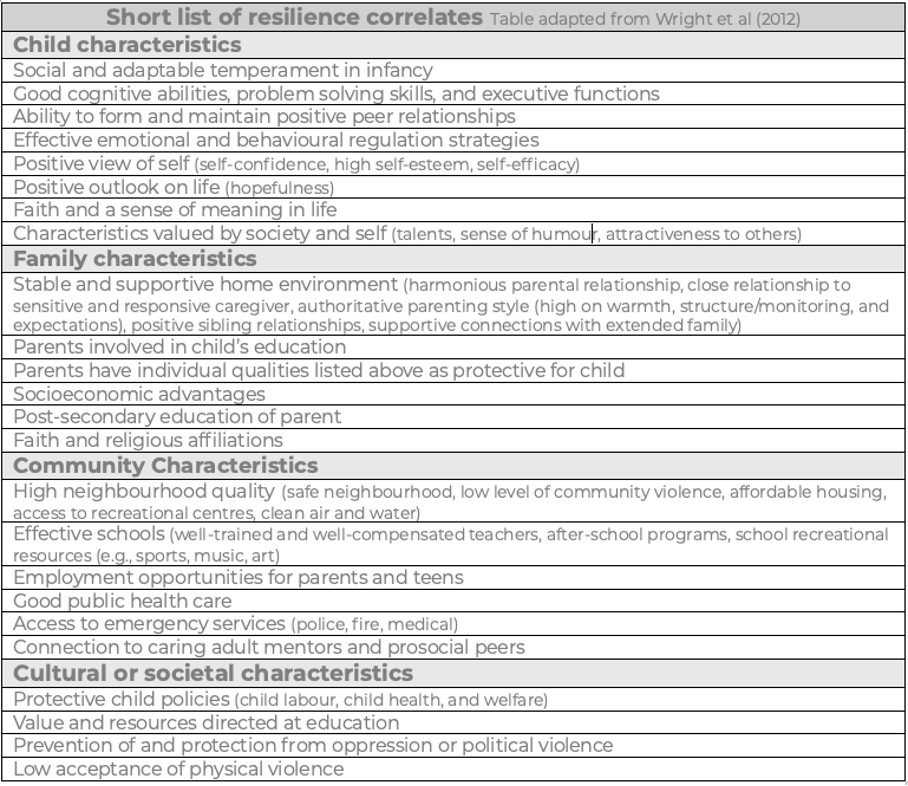

When we review literature about resilience, so many of the correlates to resilience are to do with the community around a person. As you can see in this ‘short list of resilience correlates’ in Table 1, even the list of ‘child characteristics’ are mostly dependent on the list of family, community, and cultural or societal characteristics.4 A quick glance at this list confirms that ‘resilience’ is a communal process we don’t get to choose. It is not an individual act of agency. If we instead notice what this list builds around a person – I would suggest this list outlines communal processes that build a sense of safety for all the members of that community.

Table 1: “Short-list” of correlates of resilience as per Wright et al (2012)4

And yet – so often ‘resilience’ is used to describe individual capacity or competence. Some thinkers critique this as a kind of neo-liberal social policy that highly values “individual attributes that are integral to autonomy, self-invention, and choice”5 Resilient people, the logic goes, are good contributors and customers, good wheels in our economy. Although autonomy and opportunity to choose are part of health, they seem to be words that only the privileged think of as always accessible. Seen through this lens, the word resilience could perhaps be closely aligned with socioeconomic and social and emotional privilege.

Perhaps it would be better for us to measure the community capacity to comfort and encourage its own members. Perhaps individualising distress as personal psychopathology has let us ignore the need to prevent harm or pursue justice. Perhaps there are communal processes that heal. These are not about individual choice, autonomy or ‘resilience’. They are about relationships, beliefs, behaviours, cultures and contexts that build our sense of safety in the world.

Dr Nicole LePera describes this saying:

“The New Generational Wealth is growing up in a home where people apologise and repair after conflict… It’s witnessing respect between your parents, even if they are no longer together… [It’s] knowing that love doesn’t leave when things get hard. It’s the quiet understanding that that your worth isn’t tied to productivity, perfection, or performance. It’s growing up knowing that softness and strength can coexist, and that the foundation of a home isn’t built on silence and submission, but on honesty, repair, and respect…”6

As a family doctor, I sometimes think that public policy is designed by people who have never been sick. People who have never needed others to lift them up, never needed to ask for help, never felt so tired or ill they couldn’t make a choice, never needed to repair relationships with people who they continue to live with in community, or never had to manage complex layers of distress. Many public policies assume internet access; enough money to buy food that follows health advice; enough nurturing to not need addictive substances to cope; enough workplace support to take maternity leave; enough community safety to go outdoors for exercise; enough financial freedom to ‘move on’ and make a new beginning; enough emotion regulation to navigate the frustrations of learning with a growth mindset; even enough safety in their bed to be able to sleep.

I have spent the last 15 years researching the idea that building Sense of Safety is a more inclusive, active, and communal way to describe health.1,7 [1] This has become the Sense of Safety Theoretical Framework for whole person care.8 Sensing we are safe is personal, and it is dependent on the people and context we are in. Sensing we are safe is relevant for our biology, our sense of self, and our relationships.1,9-12 Sensing we are safe is a life raft above the stormy seas of life. It is a whole person and communal experience. When we lose our sense of safety it is a communal responsibility.

Dr Judith Herman, who first identified trauma in the home, has recently published a book where she reminds us not to individualise ‘trauma’ as within a person – and instead to search for ways to make our communities more just, more mutual, more accountable, less tyrannical, and less patriarchal.13 She calls us towards healing, repair, restitution, rehabilitation, and prevention.13 This is a communal vision of what heals individuals within their communities.

Unlike the word resilience, the ordinary English phrase ‘sense of safety’ embeds the internal and embodied experience of the person who senses within their community. It places them as the one who names their experience. It brings together appraisal of internal and external threat, appraisal of capacity to cope with that threat, perception of social support, and capacity to make meaning out of a situation.8 It is a strength-based and healing oriented goal of care. Focussing on building sense of safety naturally draws attention to personal, communal, contextual, and meaning-making strengths and resources for coping and growth.1

In my doctoral research14,15 I asked people with a lived experience of mental illness (n=9), rural and urban Australian General Practitioners (n=11), multidisciplinary mental health clinicians (n=18) and Indigenous academics (n=2) a question: “what does the phrase ‘sense of safety’ mean to you?” Their responses were very integrated- describing concurrent awareness of themselves, other people and their context. They said things like:

“Feeling secure withing myself, my community, and the wider world” (mental health clinician)

“Feeling safe for my culture, spirit, identity” (indigenous academic)

“Being safe, and feeling that in all aspects of my being” (indigenous academic)

“Feeling safe in all aspects of life: being respected for your mind, body, spirit” (lived experience)

Participants in this study also mentioned relationships (“Feeling of having supportive people around me” – mental health clinician), their body (“Being physically and emotionally comfortable” – mental health clinician), inner experiences (“feeling secure within myself” – mental health clinician), context (“feel safe in this space” – general practitioner), culture (“secure in my culture, identity, environment, and femininity without persecution” – indigenous academic) and community (“to have others to reach out to when I am overwhelmed” – mental health clinician).

Participants also described the nature of the connections between self, other, and context – describing connections to other people that were respectful, available, tuned in, and “with you” and “on your side” and helped them to feel free to be themselves and express their needs. Participants noticed the culture of how others interacted with their context and described their engagement with their context with phrases like:

“It means an individual feels comfortable in their environment and in turn within themselves to step outside their comfort zone and try something new” (mental health clinician)

“feel free to try something risky” (lived experience)

“I have the resources needed to deal with the demands of my environment” (mental health clinician)

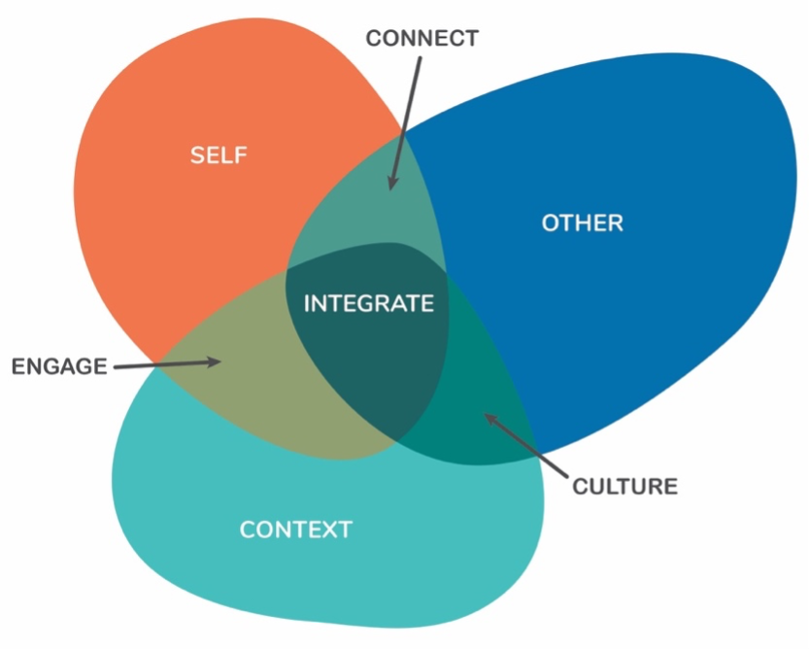

Sense of Safety is depicted in the image below as an integrated personal experience at the centre of community, context and self. Every part of that whole contributes to a person’s Sense of Safety. This is so much more than the thin description of function – ‘resilience,’ and it turns attention towards deep strengths and resources (unlike the word vulnerable).

Figure 1: Broad concurrent awareness: mapping responses to “what does the phrase “sense of safety” mean to you? Reprinted with permission from Lynch (2021) A whole person approach to wellbeing: Building Sense of Safety. (Available on Audible now)

Sensed safety changes our physiology, it protects us from chronic inflammation and stress hormones, it enables us to concentrate and learn, and accurately sense other people and assess whether they are trustworthy.1 It holds within in it an implicit sense of our own value, our dignity, our place in the world. It also helps us engage with our world. The Sense of Safety Theoretical Framework is not just about feeling comforted and safe.8 It is not just about getting comfortable away from stress or threat. It is feeling safe enough to face reality. Safe enough to grieve our losses and pain. Safe enough to reach out towards others, to ask for help, to express our needs, and to engage with life. Safe enough to grow. Safe enough to give.1

Judith Herman, who first described the key aspects of trauma informed care, described “establishing safety” before people could face the tasks of “remembrance and mourning”, and “reconnecting with ordinary life”. These tasks of mourning and reconnecting are built on a foundation of feeling safe. As I mentioned in an earlier essay, the Circle of Security parenting training describes two aspects to safe caregivers – safe haven to help someone by welcoming and comforting them, and secure base to step out from them into the world.16 Sensing we are safe is a platform for courage – and there are endless possibilities for how courage changes how we live our lives.

Staying aware of what builds Sense of Safety in our community and in a whole person is a way of paying attention that does not individualise responsibility to get well or ‘bounce back’. Rather than describing people as ‘resilient’ maybe we could focus more on whether their community is just and kind enough to build sensed safety. This kind of community offers the dual gifts of comfort to heal and courage to live. Will you join me in staying fascinated about how communities build enough courage to engage with the world?

The author would like to thank Rebecca Moran for her review and comments on an earlier draft.

[1] The University of Queensland School of Medicine Low Risk Ethical Review Committee (2017-SOMILRE-0191) with an amendment in 2018 (2018000392) to allow inclusion of iterative feedback from international consultation that year. Phase Two ethical approval was provided by the University of Queensland School of Medicine Low Risk Ethical Review Committee (2021/HE002268)

About the writer

Dr Johanna Lynch MBBS PhD FRACGP FASPM Grad Cert (Grief and Loss) is a retired GP who writes, researches, teaches, mentors and advocates for generalist and transdisciplinary approaches to distress that value complex whole person care and build sense of safety. She is an Immediate Past President and Advisor to the Australian Society for Psychological Medicine and is a Senior Lecturer with The University of Queensland’s General Practice Clinical Unit. She spent the last 15 years of her 25 year career as a GP caring for adults who are survivors of childhood trauma and neglect. She consults to a national pilot supporting primary care to respond to domestic violence.

An invitation to see healing orientation as the new normal.

Read moreAn invitation to be fascinated with what builds enough courage to engage with our world.

Read moreAn invitation to resist ignoring invisible causes of suffering and strength.

Read moreAn invitation to consider the links between wholeness and healing.

Read moreCongratulations to Rebecca Moran and team from the Big Anxiety Research Centre for TheMHS 2024 Lived Experience Led Storytelling Award!

Read moreAn invitation to consider the biology of belonging.

Read moreAn invitation to see social determinants of health in a new light.

Read moreAn invitation to critique current understanding of mood as disorder.

Read moreAn invitation to see the interconnected embodied whole.

Read moreby Next Generation Researcher Network

Read moreApplications closed for 2024 round

Read moreA Call to Action to [Re]form National Mental Health and Well-Being, March 2024

The ALIVE National Centre Next Generation Researcher Network Capacity Building Funding Scheme 2024

Read moreTo address capabilities needs, career pathways, conditions in research organisations and identify lived-experience approaches and practices for research integration

Read moreThis handbook has been co-designed by members of the Co-Design Living Labs Network.

Find out more about the noticeboard feature and how to contribute

Read moreA capacity building and career development initiative of the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation

Read moreThis is a monthly event focused on bringing people together to discuss and translate the findings in mental health research.

The ALIVE National Centre is funded by the NHMRC Special Initiative in Mental Health.

The ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation acknowledges the Traditional Owners of the land on which we work, and pay our respects to the Elders, past and present. We are committed to working together to address the health inequities within our Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.

WARNING: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers are warned that this site may contain images and voices of deceased persons.

This map attempts to represent the language, social or nation groups of Aboriginal Australia. It shows only the general locations of larger groupings of people which may include clans, dialects or individual languages in a group. It used published resources from the eighteenth century-1994 and is not intended to be exact, nor the boundaries fixed. It is not suitable for native title or other land claims. David R Horton (creator), © AIATSIS, 1996. No reproduction without permission. To purchase a print version visit: https://shop.aiatsis.gov.au/

The ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation is funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) Special Initiative in Mental Health GNT2002047.

ALIVE Next Generation Researcher Network Application Form Click here

For University based research higher degree students, early/mid-career mental health researchers

ALIVE Lived Experience Research Collective Application Form Click here

For University and community based lived-experience or carer-focused mental health researchers at all career stages

ALIVE Collective Application Form Click here

For any individuals or organisations with a general interest in supporting the special initiative in mental health

ALIVE Implementation and Translation Network (ITN) Application Form Click here

For sector, service delivery organisations in mental health serving people across the life course and priority populations

If you have a general enquiry about The Alive National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, please submit an enquiry below

Not a member of the ALIVE National Centre? Register now

ALIVE Next Generation Researcher Network Application Form Click here

For University based research higher degree students, early/mid-career mental health researchers

ALIVE Lived Experience Research Collective Application Form Click here

For University and community based lived-experience or carer-focused mental health researchers at all career stages

ALIVE Collective Application Form Click here

For any individuals or organisations with a general interest in supporting the special initiative in mental health

ALIVE Implementation and Translation Network (ITN) Application Form Click here

For sector, service delivery organisations in mental health serving people across the life course and priority populations

If you have a general enquiry about The Alive National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, please submit an enquiry below